Freewill vs. Sinful Nature

A full recognition, side by side, of the freedom of the will, the evil consequences of the Fall, and the necessity of divine grace for salvation. Individual writers, or even the several sections of the Church, might exhibit a tendency to throw emphasis on one or another of the elements that made up this deposit of faith that was the common inheritance of all. The East, for instance, laid especial stress on free will: and the West dwelt more pointedly on the ruin of the human race and the absolute need of God's grace for salvation. But neither did the Eastern theologians forget the universal sinfulness and need of redemption, or the necessity, for the realization of that redemption, of God's gracious influences; nor did those of the West deny the self-determination or accountability of men. (B. B. Warfield)

This new heresiarch ["heresy"] came, at the opening of the fifth century, in the person of the British monk, Pelagius. The novelty of the doctrine which he taught is repeatedly asserted by Augustine, and is evident to the historian; but it consisted not in the emphasis that he laid on free will, but rather in the fact that, in emphasizing free will, he denied the ruin of the race and the necessity of grace. This was not only new in Christianity; it was even anti-Christian.

The controversy began when the British monk, Pelagius, opposed at Rome Augustine's famous prayer: "Grant what Thou commandest, and command what Thou dost desire." Pelagius recoiled in horror at the idea that a divine gift (grace) is necessary to perform what God commands. For Pelagius and his followers responsibility always implies ability. If man has the moral responsibility to obey the law of God, he must also have the moral ability to do it.

Augustine's view of the Fall was opposed to both Pelagianism and Semi-Pelagianism. He said that mankind is a massa peccati, a "mess of sin," incapable of raising itself from spiritual death. For Augustine, man can no more move or incline himself to God than an empty glass can fill itself. For Augustine the initial work of divine grace by which the soul is liberated from the bondage of sin is sovereign and operative. To be sure, we cooperate with this grace, but only after the initial divine work of liberation.

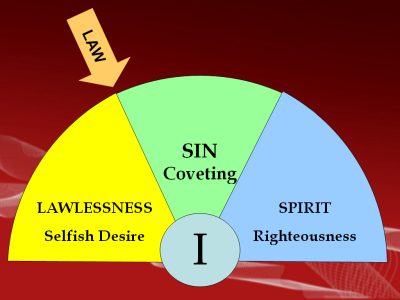

Augustine did not deny that fallen man still has a will and that the will is capable of making choices. He argued that fallen man still has a free will (liberium arbitrium) but has lost his moral liberty (libertas). The state of original sin leaves us in the wretched condition of being unable to refrain from sinning. We still are able to choose what we desire, but our desires remain chained by our evil impulses. He argued that the freedom that remains in the will always leads to sin. Thus in the flesh we are free only to sin, a hollow freedom indeed. It is freedom without liberty, a real moral bondage. True liberty can only come from without, from the work of God on the soul. Therefore we are not only partly dependent upon grace for our conversion but totally dependent upon grace.

Link to next sermon

Link to next sermon

Link to other sermons of Chris Benjamin

Link to other sermons of Chris Benjamin